This week’s blog post was guest-written by Martin Macmillan, CEO & Co-Founder of Pollen Velocity Capital.

The investment community in Silicon Valley and beyond is obsessed with the concept of unit economics. At its core, it comes down to two key metrics, and can be applied to almost any business where growth through acquiring new customers is important.

- How much is the user acquisition cost (UAC)?

- What’s the expected lifetime value (LTV) of the customer?

In the app economy, there are a number of characteristics that make unit economics easy to figure out relative to traditional industries, where the acquisition costs are transparently understood, and the LTVs are fairly short (i.e., less long-term uncertainty).

In the app economy, huge scale can be achieved almost instantly. With omnipresent advertising platforms like Facebook and Google, it becomes easy to reach huge audiences for an app or game without the traditional shackles of distribution of a physical product.

There is a distinction to consider between apps offering purely digital content and those who act as a delivery interface between the digital world and the physical one. Examples include Uber, Deliveroo or TaskRabbit, where LTVs are measured over longer periods of time.

When the content is purely digital from end to end (e.g., a strategy game monetizing through in-app purchases and ads, or a mindfulness app with new content available to download over time) then the economics can get much more predictable. Publishers can start to draw comparisons toward huge frictionless markets like the global foreign exchange market—which is highly commoditized and liquid. Whilst the mobile advertising market is structurally different, at scale you can start to consider audience profiles being somewhat commoditized based on deep insights into app user behavior—such as in-app actions like completing a tutorial—as well as which apps are installed, retention over time and spending patterns.

User Acquisition Cost

This is the easy part of the unit economics equation—how much does it cost to acquire or “buy” a user or install and and get them to try out an app on their smartphone? Facebook and Google have pretty sophisticated audience-sizing and bid estimate tools that allow marketing teams to figure out what their acquisition costs will be. The traditional metric of CPI (cost per install) is slowly losing out to CPA (cost per action) where the more sophisticated advertising platforms allow optimization on not just the install but a particular post-install action within an app. This could be completion of a tutorial, spending a certain amount of time playing a game, or making a purchase.

The issues here are acquisition costs. They are not static nor do they scale linearly. The mobile app industry is a dynamic marketplace with multiple factors at play, including how many others are bidding to reach the same audience at that time. Contrary to normal economic theory, with app installs the more users you buy, the more you pay. You are bidding ever higher costs to reach an audience that becomes scarcer over time.

Lifetime Value (LTV)

This is where assessing costs gets trickier. At one end the spectrum, it can be incredibly easy. If a mobile developer sells a paid app or game with no additional monetization, then the LTV is the developer proceeds paid out after platform fees. All of the LTV is earned as soon as the buyer clicks to purchase the app.

However, in the much more popular world of freemium apps, LTV becomes much harder to calculate and many developers fall down at this hurdle. Any app is going to have different funnels that need to be understood, such as conversions from downloads to paying customers, paying customers into repeat purchasers etc., and very importantly the retention profile which gives insights into how engaging an app is and how often users return and stay engaged.

It is irrelevant to attempt model behavior of a single user in a freemium environment, so it’s necessary to take a step back and model the observed behavior of a cohort of users, normally 1,000 or more. This is typically done by acquiring users through paid channels like Facebook and then seeing how these users behave over time. Key things to observe and track are:

Retention: This form of retention – classic retention and not rolling retention – is normally quoted as a percentage profile of returning users over a period of time, for example D1: 40%, D7: 20%, D14: 15%, D30: 10%, D60: 5%

ARPDAU: This is the total daily revenue earned divided by the number of active users on that day.

Virality: For each paid user acquired, there is generally an additional halo effect of other unattributed users acquired at no cost, known as “organics”. Organics could be acquired by virtue of added visibility from things like an app’s position in the app store charts, social sharing within the app, word of mouth, etc.

Does paid acquisition work for my app?

Simply put, if a developer has a formula where their LTV is higher than their CPI, then they are able to use paid channels to acquire users profitably for their app. However, it’s important not just to figure out if they have a positive acquisition formula for ROI, but to look behind the metrics to gain insights into what growth could be achievable and in what timescale.

The more confidence a developer has in their metrics, the more confident they can be in making and implementing their investment decisions. Ad attribution and constant analysis of cohort behavior is imperative. This is not a set-and-forget situation.

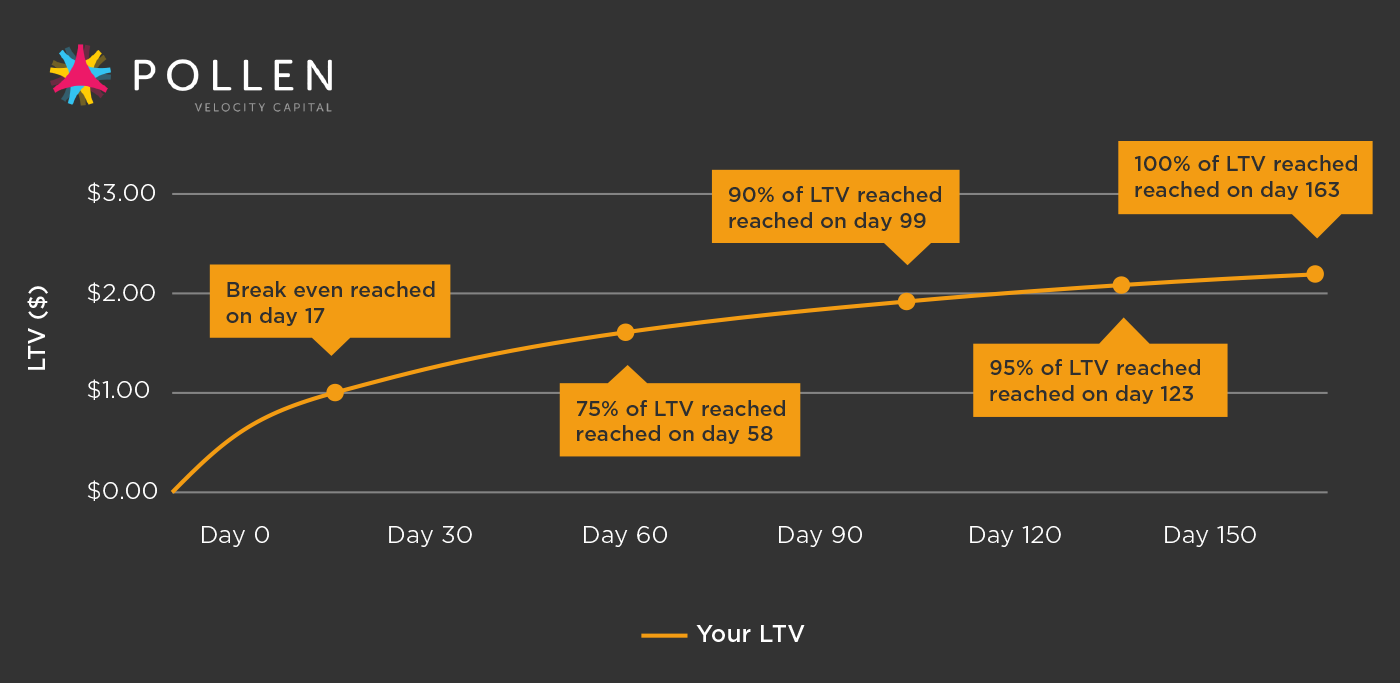

Many developers think of LTV as a static metric and don’t consider the shape of the LTV curve or the point at which the LTV is deemed to have been delivered. Below is an example of a positive ROI in UA where if the CPI break-even point is achieved on day 17, then the app delivers an additional $1.17 of LTV value over the next 146 days. If you consider the financials, you are making a trade where you invest $1.00 on day one and get $1.96 back in 90 days. Thus, this example makes a nearly 100% return on their investment in just 90 days.

When bidding on CPI/CPA, it’s important to keep in mind the minimum returns you might expect to make. They may wish a threshold beyond what they are not sufficiently confident in the metrics to continue to invest.

Another consideration is the timing of the cash flow. Advertising is generally paid for as it is delivered, so you need to plan how this is financed, either from venture capital, or using revenue recycling—i.e., using the funds accrued but not yet paid out by the platforms to fund the UA spend by working with a company like Pollen VC.

In conclusion, having a deep understanding of your unit economics is imperative if you are going to get the most out of a paid UA strategy. Constant monitoring and vigilance over campaigns to ensure they are performing as expected is key. And once you have confidence in the metrics and see them delivering predictable results, you should double down and capitalize on the opportunity.

Try out the Pollen LTV Calculator at https://ltvcalculator.pollen.vc.

Pollen Velocity Capital finances growth of high potential app and game developers. By providing mobile developers early access to their app store and advertising revenues, Pollen enables developers to scale quickly and efficiently through reinvestment of earned revenues into user acquisition. Find out more at https://pollen.vc.

About the Author

Martin Macmillan is Co-Founder and CEO of Pollen Velocity Capital, a fintech company granting developers faster access to their app store revenues, enabling them to rapidly reinvest their earnings back into their business. With over 20 years’ experience launching and building technology businesses, and having experienced first-hand the growth challenges and lack of financing options open to developers, Martin developed Pollen Velocity Capital to marry traditional financial markets and technology to create a disruptive new business model for the app economy.